The journey of sending off your child to college, joining the military or other life transitions after graduation from high school can be one of the most emotionally excruciating transitions as well as proud moments for parents or parental figures. Just as there is nothing that truly compares to all a person puts into raising a child as a parent or guardian, there is nothing that truly compares to all a person adjusts to at the point when their young adult embarks on the bridge to their own life.

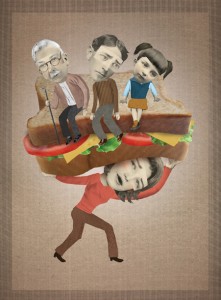

This will be the first in a series designed to help the parent, with some insights available for the young adult, through the college transition as I go through this transition myself. It is important to discuss here because caregivers, especially sandwich generation caregivers, can play other roles in life which should also be acknowledged. As an adult Third Culture Kid, some of what I share will be especially helpful to adult TCKs and adult Cross Culture Kids, but this series is written for all going through this transition. For the college-bound and college students with a global nomad background and for parents as figures of support through this transition, Tina Quick’s The Global Nomad’s Guide to Univeristy Transition is a valuable resource.

This series will be about the transition parents go through in redefining their role as parents and their relationships with their young adult children entering college. The voice used in this series will be genuine and from the moment of experiencing these things and not only after I have processed each stage of the journey. I hope that by doing this, it can prepare some of you for what you may experience and give affirmation that you are not alone.

Part One – What I Wish Someone Warned Me About the Send Off: Perspectives from my RAFT

Tomorrow, my son will be moving into what will be his dwelling place for the next two semesters. Preparing for it involved preparing him as well as myself. In the few weeks leading up to this day, I started doing what becomes instinctive for parents, preparing your child for all the practical things for college living. As any other parent, raising my son itself was preparing him for this moment and my style of parenting always involved using big and small opportunities to equip him with various skill sets and useful knowledge both practical and for social relationships. That was the teacher in me. The TCK in me started to refer to the Pollock-Van Reken RAFT (detailed below*) from Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds as a type of “checklist” and Quick’s Guide to ensure I was preparing him holistically.

Because you don’t stop being a parent to your child as a young adult and your child will not stop being your child, it is equally important for parents to also build a RAFT for themselves through this transition as well.

Tina Quick does a very thorough job in laying out how to build a RAFT* to support the college bound student and has a useful chapter for parents about the diverse range of what can be expected in the parent-child relationship during the summer before college and the adjustment period after college starts. I want to add that because you don’t stop being a parent to your child as a young adult and your child will not stop being your child, it is equally important for parents to also build a RAFT for themselves through this transition as well.

Not only is it important to move through this transition and avoid unresolved grief, the importance of which Pollock and Van Reken discuss in Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds. For the relationship between the parent and child to evolve in a fruitful way, the parent must also have a way to process the internal transition of redefining the role as a parent as well as the external relationship with the child.

The RAFT* for parents going through this transition may look different for each parent and parent-child relationship due to different parenting styles, cutural standards and ways of expressing oneself. There are four things I wish to share about the internal process of redefining my role as a parent, which some parents may need to prepare and establish a support system for as they move through this transition on their RAFT.

I wish someone warned me that I’d feel actual pangs of hollowness that come and go during the transition to sending off your adult child to college. This most likely also applies when a parent sends off an adult child joining the military, or moving elsewhere to start some other life transition. I’m here to tell you that it’s going to hurt, at least for a period while you are adjusting. Years ago, I knew this was going to be hard. However, knowing it is going to be hard is not the same thing as the actual emotional experience of it. It’s not a constant non-invasive phase in the adjustment process that you just have to wait out. It can be an actual pang that you feel that you have to really work through.

I’ve taken for granted that the house will always have his presence, perhaps not rationally, but emotionally.

Daily regular activities, like falling asleep, waking up, walking around the house, turning on the faucet suddenly felt hollow. I found myself in tears at the thought that the house would suddenly be lacking my son’s piano and guitar playing at various times during the day or late at night while I fall asleep, for longer periods of time while he is living elsewhere. Not being able to walk into his room to say good night face-to-face while he hugged and kissed me back as a little child, through the later years of a more detached “good night mom,” (with a now-please-let-me-have-some-privacy” tone typical of teens forming their own identity) feels really lonely. It’s not just a sleep over either. I’ve taken for granted that the house will always have his presence, perhaps not rationally, but emotionally. Much of the difficulty of this transition is the emotional process of what you conceptually prepared for.

“Home” to me always meant having my son at home physically. The knowledge that he will be elsewhere for an extended period of time is an emotional dichotomy.

I wish someone warned me that “home” will become more fluid from now on. Building and maintaining a home is a major aspect of the role of parenthood. The concept of home by default involves an identification of who comes home to the home. This is why the little things like falling asleep, turning on a faucet, and other little things I do daily at home suddenly feels sad. The layout of the physical house is the same and realtionally, I am still my son’s mom. However, “home” to me always meant having my son at home physically. The knowledge that he will be elsewhere for an extended period of time is an emotional dichotomy. I’ve taken for granted that the house will always have his presence, perhaps not rationally, but emotionally. Home now will have to be where we will be together even though some parts of the year, we’re apart. Yet “home,” at least as the physical place where you are not a visitor, will also remain “home” for my son when he is back, even though during the school year while he has his belongings elsewhere, he is technically “visiting.”

Home now will be different for my son and for me. It will not be in the same physical location, but emotionally, being home is also when we are together, whether I visit or he visits. A physcal home that has history of us being together under the same roof is an option but not necessarily obsolete because we will be geographically apart. Home now involves different aspects that will require fluidity. While it was more simplistic to have home be the same as each others physically and relationally, this redefintion of home is as genuine and significant, but it is a painful process right now.

I wish someone warned me that the change in my role as a mother is really rough emotionally. This is another thing that is easier to have a concept of than to actually experience. Ive taken it for granted that my grocery list will always plan to feed my son as a member of the household. It feels lonely to think that I can still buy things for him, but I will be sending it as a care package while he is away. The same goes for managing his education. When he graduated from high school, I graduated from having his mandatory education under my watch. It all should be a completely freeing feeling, but at this point right now, it is still a shock to my system and I was not asking to be liberated from it all. This adjustment is hard emotionally even though rationally I knew this was coming up.

There doesn’t seem to be an instinct for ceasing to guide and protect and it takes an emotional effort to adjust this instinct for the college years and beyond.

While raising my son, whenever an opportunity arose that I could use to teach him a new skill, I would, such as how do a simple repair for a toilet leak, how to change oil in a car, how to prepare a healthy meal, and how to manage and balance time between what you’d like to do vs what you have to do. Logically and instinctively, my interaction with my son was always in preparation for him to become independent. The guidance and protection parts of my role as a parent involved my behavior and my speech being geared towards him ultimately separating and having the skills and knowledge to care for himself independently. I believe it’s a primal instinct to do this, as much as nurturing and loving a child is.

It’s still a shock to my system however, to be at this point of my role of what I’ve been doing instinctively for almost 18 years coming to an end. There doesn’t seem to be an instinct for ceasing to guide and protect and it takes an emotional effort to adjust this instinct for the college years and beyond. I understand that he has some basic skills now to be independent but it still feels anti-instinctual to just cease what I’ve been doing. It seems that I will need to work on making the guidance role more subdued from now on and hope that the seeds I have planted for practical, emotional, relational, spiritual, financial, physical and other purposes will just continue to grow.

…Knowing it is going to be hard is just a surface scratch to the actual pain of experiencing it. You may need to prepare a serious support system for or plan coping mechanisms ahead of time for to get you through the “hollow pangs.”

I wish someone warned me about the pain and sadness that come before the victories and celebration. People always talk about the end result, “It was hard but I adjusted.” “Now, he has his bachelor’s degree and he’s about to start a paid internship that can lead to a permanent job. I’m so proud of him!” I’m here to tell you that before all of that, you may go through a period of extreme sadness. Years ago, I knew this was going to be hard. But knowing it is going to be hard is just a surface scratch to the actual pain of experiencing it. You may need to prepare a serious support system for or plan coping mechanisms ahead of time for to get you through the “hollow pangs.”

Before I close, I want to also share how the RAFT may look for the internal adjustment for the parent and the parent-child relationship.

The RAFT stands for the following:

R= Reconciliation, which “includes both the need to forgive and be forgiven” (Pollock, D. and Van Reken, R., Third Culture Kids, Growing Up Among Worlds, 2009. p. 182.).

A= Affirmation, which involves “the acknowledgement that each person in (a) relationship matters,” (Pollock, S. and Van Reken, R. 2009. p 182) including family members, significant adult figures or role models, and friends.

F= Farewells, which includes farewells to “people, places, pets, and possessions” (Pollock, D. and Van Reken, R., 2009. p 183).

T= Think Destination, which refers to considering what you need to prepare for both “internal… and external…resources for coping with problems” that may be encountered after arriving at your next destination. (Pollock, D. and Van Reken, R., 2009. p. 184).

The following is my application of the Pollock-Van Reken RAFT for the internal process of this transition as a parent and between the parent-child relationship:

Some of this may not need to happen before your child leaves, but if anything is unresolved, it could determine how your child will visit after leaving.

Reconciliation – If there are unresolved matters that have weighed heavily on the relationshp between you as the parent and your child, it would be healthy to address them with the goal of coming to terms with it before your child goes to college. Some of this may not need to happen before your child leaves, but if anything is unresolved, it could determine how often your child will want to visit after leaving.

Internally, if there are any areas where you as a parent need to forgive yourself for mistakes you’ve made, it is also important to work through them if you have not yet. No parent is perfect and we all have made mistakes. If you need to seek forgiveness from your child, it may help to do this before your child leaves because again, it may determine how your child visits after leaving.

Affirmation – Communicating about the various significant pleasant memories from the time spent with your child and what you cherish about your bond with your child can help affirm special aspects of your child’s character and personality. This may help how he or she relates and builds relationshps with new people he or she will be encountering.

Internally, it is important to cherish and congratulate yourself for your own accomplishment that led up to this new life stage for your child. Before that may happen, however, it may be important to acknowledge and validate for yourself the losses you feel during this transition. In a way, sharing what has been painful through this process is a way of grieving them so that I can move forward. I invite you to also reflect on, allow yourself to completely feel and, if you feel comfortable, share here what are the hardest moments for you.

Farewells – As far as the farewells my son and I face together, looking back, we have always done this throughout my son’s chldhood and adolescence as he entered each new stage of his development. We often discuss changes in his relationships with people in his life. We have reminisced about special places that have come and gone. My son isn’t the type to be attached to a geographical place unless there is significant memories attached to it, which may now be more associated with moments with his friends. We are in the process of determining how I will takeover his share of care for the pets. I will need to let go of certain souvenirs from his childhood.

Internally, I am still working through this. Much of what I share above is what I am working through as I bid farewell to how parenting has been for me, in sharp contrast to my role now as a parent of a college student. It was a reassuring experience for me, however, when I was present during one of the times my son hung out with close friends. My son as well as his friends seem to be very genuine about their friendships yet realistic about how often they will be seeing each other. My son also has taken intiative to bid farewell to other special people in his life he has not seen in a while before leaving and has made efforts to make sure I will be ok. All of this is helping me with my own farewell to my previous role as a mother.

Think Destination – Between my son and me, we have discusssed how he and I each feel about the next stage in life. I told him about the plans I have for starting a business on the side that involves something he’s known that I love doing and the possible nearby cities I plan to transition to after he leaves for college. Yes, I’ve also expressed how much I miss him (probably more than I should have), but I hope that I have also expressed well enough about other passions and goals that I have.

Internally, the emotional impact of how my parental role will change is what I have been avoiding. My son has resources for the next stages of his life, but internally for me, it’s completely foreign territory. I’ve been in college. As much as my dad now will guide me through this transition, I have never been through it. What I can say at this point is that translating the instinct I’ve had in equipping him with skills and knowledge that will help him take care of himself into equipping him for this next life stage is what propels me forward emotionally. I just have to attach new emotions to this stage that involve more unfamiliarity and change. Each step of parenting as your child ages is new of course, but this transition is completely different.

There is no emotional “pre-nup” equivalent for the parent-child relationship. There isn’t supposed to be one.

Although I wished people warned me about how tough this transition can be, I think that in the end, the emotional process of this would still be difficult. There is no emotional “pre-nup” equivalent for the parent-child relationship. There isn’t supposed to be one. For those also going through what I am, we are supposed to risk feeling this pain because becoming a parent involved an investment of so much of ourselves. There shouldn’t be some type of safeguard to prevent parents from feeling the pain when letting go. If others are going through the same thing as I am about to go through tomorrow, please know I am going through this with you and yes, it hurts like crazy. Allow yourself to experience it and as you move forward, I will be also. Grab your tissues, let it out, reach out for your support system and find all the strength you have within you to get through this. And we will get through this.