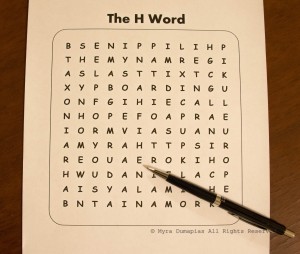

I wanted nothing to do with it what-so-ever. It was the dirtiest word anyone could ever toss in my direction. If my mind was ever close to the door where this word was waiting on the other side, I turned around and walked away. It was a cold arrogant intrusive slap in my face.

When a social worker told me about the option for hospice care for my mother, I immediately thought of the competition businesses for the elderly must find themselves in. As I listened to the representative for home care services and, on a separate appointment, the representative for hospice care, I thought about what PR skills they must have to “win the bid.” It wasn’t so much that they were pushing their product, but it was the lack of empathy I saw in their eyes. As a social worker, I was familiar with the clinical approach they must take and it felt downright dirty to be on the other end of it.

To the social workers and case workers, it was about intake forms, contracts and signatures. To me, this was a brush with strangers who knew nothing about my mom and how she survived doctors’ predictions about her death more than once before. To me, they knew nothing about their client and I did not care to learn more about their product.

I was so angry that I felt numb towards the young hipster doctor who asked me with a perplexed face why we wanted to keep my mother alive the day she was brought into emergency room services. He assessed the complete value of her life based on her current quality of life within a matter of three, maybe five minutes in front of the persons who had been caring for her every day for several years. Just the day before, she was telling me about a recipe she concocted that she wanted me to try.

To the emergency room doctor, my mother was a patient in bad shape compared to able bodied patients who were healthier. He practically left her for almost dead and expressed it. We were dealing with a young arrogant doctor in unusually short and tight black pants donned in a lab coat of stolen permission to be insensitive in a moment that only lasted several minutes for him. To me, this was my mother whom I’ve known since the day I was born.

There was also an encounter with a hospital staff worker interrupting my mother while she was sharing some final words with my son. When I spoke to him on the side, he informed me she was ordered for a move to a different wing of the hospital and assured me the wing they were moving her to was not for dying patients. We asked for some warning and respect for the moment. His supervisor insisted she told the family ahead of time but then told me she would speak to the staff after realizing what my main point was.

Newborns in hospitals have clean and monitored dedicated wards demarcated with huge windows that serve as the greeting place for human beings that meet for the first time. However, patients who may be facing the end their life and final goodbyes can slip through holes of management that cares little about the patient’s personhood.

Newborns in hospitals have clean and monitored dedicated wards demarcated with huge windows that serve as the greeting place for human beings that meet for the first time. However, patients who may be facing the end their life and final goodbyes can slip through holes of management that cares little about the patient’s personhood. The rest of the world is on pause when you witness the first hours or days of a tiny human being simply breathing, sleeping or moving in the blanket. No one wants to face the reality of what may be the last last breath, night or movement of someone one has childhood memories with. When management does not create a system of care for the end of life stage as adequate as that for the beginning of life, there is something drastically and ethically wrong about the picture.

Newborns in hospitals have clean and monitored dedicated wards demarcated with huge windows that serve as the greeting place for human beings that meet for the first time. However, patients who may be facing the end their life and final goodbyes can slip through holes of management that cares little about the patient’s personhood. The rest of the world is on pause when you witness the first hours or days of a tiny human being simply breathing, sleeping or moving in the blanket. No one wants to face the reality of what may be the last last breath, night or movement of someone one has childhood memories with. When management does not create a system of care for the end of life stage as adequate as that for the beginning of life, there is something drastically and ethically wrong about the picture.

As a way to make it known to the doctors that the family was not giving up the way they seemed to, I took on an advocate role for my mother. Instinctively and in my spirit and soul, I just knew there was no way God was going to allow things to go down this way. One day, it would happen, but no way was it going down like this, so suddenly and out of the blue. No. Way.

I made it known that it was cultural differences and unfamiliarity with strangers vs. a neurological or mental incapacity that caused my mother to not give the type of answers assessing staff were looking for. I made it known her life was valuable enough to try anything that wouldn’t put her in greater risk, despite the initial assessment about her life. I made it known we were capable of helping the nurses with her care becauses they aren’t paid enough and are too overworked to always be by her side. I made it known the person who gave me life would not go through the end of her life in an environment without dignity.

When certain hospital staff members left the room, my mother would comment, “What? Do they think I’m crazy?! Do they think I don’t understand what they’re saying?”

There was so much spunk left in my mom. When certain hospital staff members left the room, my mother would comment, “What? Do they think I’m crazy?! Do they think I don’t understand what they’re saying?” The first morning after she was admitted, she pointed to an airplane flying in the sky outside her window. My father, my son and I took a look. Sure enough, it was there, but only she noticed it from her hospital bed. It was her usual way of trying to make the time go by. Throughout the entire time she was hospitalized, she just wanted to go home.

Amidst negative news, there were hospital staff members that helped lighten the situation. During that intrusive move from one hospital wing to another, a nurse shared her story about how her sister had passed away the year before and how she knew what we were going through. When my mother was brought out of the emergency room, a Filipino nurse was the first to greet us and it helped my parents feel more at home to hear Tagalog her first night at the hospital. A respiratory nurse who regularly came in would brush the hair to the side of my mother’s face while they looked into each others’ eyes during breathing treatments. Towards the very end, the releasing doctor shared his own story about the end of life care for his own father. During these moments, they all recognized my mother’s personhood. These encounters helped us see the human side of the hospital staff members also.

During these moments, they all recognized my mother’s personhood. These encounters helped us see the human side of the hospital staff members also.

When it was time for my mother to be released, it seemed the wisest option was for my mother to be released into home hospice care. I felt lost and I did not know how to even think about funeral arrangements, but out of concern for my mother’s comfort if she was really about to pass away, home hospice was the best option. Her physical condition was such that the day of the actual release, my mother’s blood pressure dipped so low that it seemed she might pass before she could even go home. Hospital staff workers remedied it, perhaps with the goal of prolonging her life just long enough that if it were to happen soon, it would happen within the comforts of her own home.

My mother did not know it at that time, but there was a terrible storm of events happening. I had to be strong enough to choose the right time to tell my father that her eldest sister had just passed away. The day my mother was admitted to the hospital, my dear aunt had a stroke and was rushed to the hospital herself. The day my mother was released from the hospital, my aunt passed away from the stroke, while she was in a coma. Our larger extended family was going through a terrible time, and my father had to temporarily leave my mother’s bedside in this condition to attend his sister’s funeral. We experienced multiple losses only a year after one of my father’s younger brothers passed away with cancer.

What served as a blessing was that my mother’s siblings had schedule their visit to see her and it happened to be around the time my father needed to leave for my aunt’s funeral. It helped my mother cope with my father being gone, who had only explained that he needed to visit his sister. We told my mother the news of my aunt’s passing when she was physically more stable. Just being home made a big difference to my mother while my father was away.

The hospice nurse my mother was assigned to worked and adjusted with us so well that she became an important part of our lives. It become so clear that home hospice care was one of the best decisions we made for my mother’s life.

The weekly visits from different hospice staff members throughout the week greatly helped my mother as well as my father. The hospice nurse my mother was assigned to worked with and adjusted to us so well that she became an important part of our lives. My father looked forward to their visits. It become so clear that home hospice care was one of the best decisions we made for my mother’s life. My mother actually healed from the two main conditions that placed her into hospice care. There was a third condition that we continued to monitor and there were a few other health issues that popped up, but the nurse helped us through them all in ways we simply were not trained for. What I also cherish is how my mother developed relationships with the hospice staff members who came regularly. They got to know her as someone who made them all laugh so hard and someone who genuinely cared about them and their loved ones.

My mother’s time in home hospice was most likely the best way she could have left us. Ultimately, my mother ended up being on hospice care for a little over one year and one month. For a while I even thought she would disqualify for hospice care. She was able to witness another full year of birthdays, watch her grandson meet more milestones as a young teenager, and spend more quality time with all of us. The cause of her death was not ruled to be related the health conditions that originally placed her into hospice care. It seemed that it was just time for her to go.

My mother knew it was her time and she demonstrated she had peace about it before the rest of us in the family did. My mother was able to say her goodbyes and final requests in the comforts of her own home. She expressed concern to the hospice chaplain about my father as the one who was most adamant against her passing, but was ready herself. When it came close to her time, she lost her ability to speak. Yet, my mother still managed to communicate her goodbyes and final thank-yous to the hospice staff workers. One hospice worker bid her regular farewell, “Dios te bendiga. See you next week.” My mother shook her head, but seemed to want to say thank you among a few other things. I found myself translating to hospice workers during their final visits what she wanted to say, as if I had a different set of ears to hear what she would otherwise be speaking out loud. She gave a thank-you-and-goodbye pat on the hand of the hospice nurse as her condition progressed and the nurse knew what it meant. My mother had help with pain management, oxygen and other tools that made the final days bearable for her.

As a family, we let my mother know she was never alone the days leading up to the last moment. We did not want to say goodbye, but we eventually came to accept it was better for her to pass away in peace than be concerned about our lack of peace and our unpreparedness. My father began to come around to speaking to her about letting go if it was truly God’s will it was her time. I also assured her that I would take care of the family and make sure her husband whom she knew as a child and whom she was married to for 47 years would be alright. As a daugher I also shared my farewells. Within a couple hours after my son spent time with her and bid his final farewells, she passed away. My father, my son and I surrounded my mother, holding her hands, praying for her and telling her we love her during her last breaths and final movements. It was as if she was waiting for all of us to have peace.

Things would have been different without home hospice care. I learned so much about something that used to be such an object of aversion for me. What I thought was synonymous with giving up was actually just a different context to keep trying everything that would not put her in greater risk or otherwise end in a bleaker situation.

The H word stands for hospice, but also for hope and for home.